JudeEsq

By F. J. Jude, Esq published on jude.ng

There is no Nigerian who does not dream of a justice system that works. A system staffed by competent, principled, courageous lawyers who were trained not only to memorise statutes but to defend real human lives. We all agree: reform is necessary. Our laws must evolve. Our courts must evolve. Our legal training must evolve.

But evolution must not become punishment.

Today, the average Nigerian law graduate is asked to endure a journey longer than medical doctors in many countries, yet offered nowhere near the same structure, supervision, or economic support. The new legal internship mandate under the proposed Legal Practitioners Bill 2025 would stretch this already demanding journey to nine years and does so under conditions that risk exploitation, poverty, and the total discouragement of brilliant minds from humble homes.

Reform should remove obstacles. Not build new walls.

And so we must ask: Why must hands-on legal training begin only after graduation, instead of being embedded into university education from the start?

The Medical Model: A Simpler, Superior Blueprint

Medicine in Nigeria despite its challenges already solved this long ago:

• Phase 1: 3 years of foundational and theoretical training inside the university

• Phase 2: 3 years inside teaching hospitals, facing real patients and real cases

• Phase 3: Housemanship supervised independence, with payment

By the time a doctor receives their licence they have lived inside their profession. They have touched their duty with their own hands.

Why should the law be different?

A lawyer’s mistakes can also destroy lives. A lawyer’s success can also save them.

The same structure would transform legal education:

Year 1 For Foundational knowledge: GSTs, philosophy, history, politics, communication skills; for a lawyer without broad understanding is like a surgeon who only studied anatomy

Year 2 and 3: Core law courses, rigorous and immersive

Year 4: Full-year chamber attachment: drafting processes, research, client relations

Year 5: Full-year court placement: supervised motions, mediation, procedure in action

Law School: Entirely practical, selecting only those who can truly practice law

However, there could be an extra year after Call to the Nigerian Bar during which a lawyer undergoes a well-paid internship at the Ministry of Justice or within the litigation and drafting departments of other government agencies. This would operate in the same manner as the housemanship year for medical doctors.

This model produces true lawyers. Not people who merely studied law.

It is cheaper. Faster. More just. And above all more effective.

Why Mandatory Two-Year Post-Call Internships Will Fail

Requiring two unpaid or barely paid years after Call to Bar is not progress. It is oppression disguised as regulation.

Here is the truth we must confront:

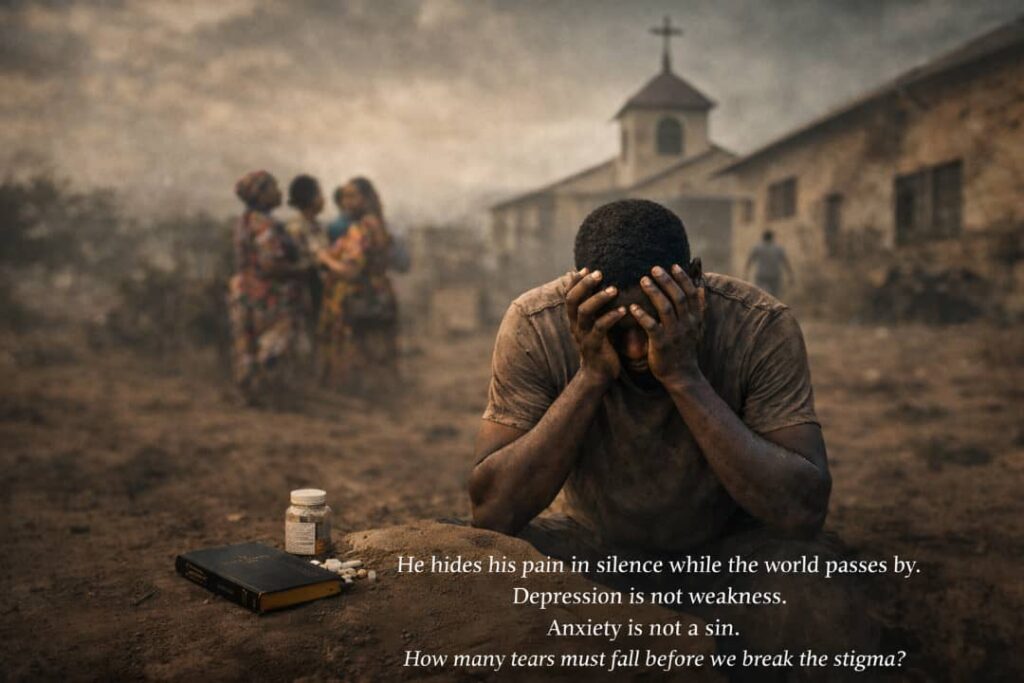

1️⃣ It punishes the poor

Most young lawyers in Nigeria already rely on family support through years of intense study. Adding two more years of income-less service will shut the door to everyone except the wealthy. The profession becomes an exclusive club, not a public service.

2️⃣ It increases brain drain

Talented youths will simply qualify abroad where training is shorter, opportunities greater, and dignity guaranteed. Nigeria will become the exporter of legal talent it desperately needs at home.

3️⃣ It will cripple chambers

Millions of naira in new staff obligations but no government support. Small chambers will collapse. Large chambers will hoard privilege. Rural and underserved communities will be abandoned.

4️⃣ It incentivises exploitation

Where supervisors hold power over continued professional existence:

• Interns become messenger boys

• Interns become cleaners

• Interns become domestic help

• Interns become prey for sexual harassment

Underpaid plus desperate plus powerless equals a dangerous environment. We must not write exploitation into law.

5️⃣ No clear curriculum equals no clear benefit

A mandatory internship without structured training is simply extended suffering. Students may sit idle while their lives pass. The nation gains nothing.

6️⃣ It delays justice for the public

Nigeria already has too few practicing lawyers. The longer we delay their ability to practice independently, the more justice is delayed for millions. Justice delayed is justice denied not only in court but in access to legal representation itself.

The Real Problem Is Not the Duration But the Design

A nation improves legal practice by improving the quality of training, not the quantity of waiting.

We should:

✔ start practical training early, not as the final obstacle

✔ pay trainees fairly always

✔ ensure real mentorship, not servitude

✔ measure competence through performance, not endurance

✔ make legal education accessible to the brightest, not only the richest

The goal is excellence through empowerment. Not excellence through exhaustion.

What True Reform Looks Like

Nigeria’s legal education should:

📍 adopt global best practices in digital courts, e-filing, and virtual advocacy

📍 expand legal aid, so every citizen can access justice

📍 create specialist pathways for modern legal needs (cyberlaw, ADR, intellectual property, fintech)

📍 introduce pro bono credits and public service incentives

📍 regulate mentorship quality through transparent evaluation

📍 guarantee a minimum living wage for any supervised legal trainee

We can build a world class legal profession without sacrificing the future of the young to do it.

Additional, Compelling Concerns and Proposals

Beyond immediate hardship the new internship mandate threatens systemic damage:

Worsening inequality of access to the profession. Legal representation should not become the preserve of the wealthy; ordinary Nigerians already struggle to afford lawyers. If only those from well off backgrounds can endure years of unpaid training, access to legal services will shrink and disparity will widen.

Greater risk of corruption and malpractice. Interns under pressure might resort to unethical shortcuts to survive overbilling clients, cutting corners in drafting, failing to follow due process. That harms clients and the reputation of the profession.

Undermining of specialization and innovation. When young lawyers are held hostage in generic internships, there is little space for them to develop niche expertise in emerging areas like technology law, environmental law, or consumer protection. Nigeria may fall behind global legal trends.

Stunting of diversity in the bar. Women, persons from rural or underprivileged backgrounds, and those with family obligations will disproportionately suffer. The profession will skew even more towards the affluent and urban elite.

Loss of public confidence. A “rite of suffering” before practice may breed cynicism. The public may begin to view legal practice as a closed, elitist institution further eroding trust in the justice system at a time when citizens desperately need fair representation.

Therefore instead of mandating a blanket two year internship the legislation should consider alternative, flexible models such as:

Shorter supervised attachments (six months to one year) with clear curriculum and assessed by independent regulators

Recognising and accrediting supervised public service e.g. legal aid, community law clinics, non profit legal work as part of training

Offering stipends or bursaries to support interns from modest backgrounds, funded publicly or through bar body levies

Creating a mentorship registry supervised by a professional body so every intern is paired with a committed, accountable mentor

Implementing continuous professional development (CPD) and refresher training for all lawyers (young and senior) to keep up with technological and social changes

A Law That Helps Everyone or a Law That Hurts Everyone?

Every legislative choice answers one question: Does this law bring Nigerians closer to justice or push them further away?

A two year post call internship mandate as currently proposed:

✘ widens inequality

✘ worsens brain drain

✘ forces young professionals into poverty

✘ endangers them with abuse and exploitation

✘ reduces access to legal services nationwide

It solves nothing. It breaks many things.

Nigeria deserves a reform that strengthens the legal profession without destroying the young people who will sustain it.

We Stand at a Crossroads

We must choose:

A system that builds lawyers through early experience rooted in university the medical style model described above

Or a system that drains potential through hardship, delay, and needless barriers

Our choice will determine:

• who can afford to become a lawyer

• which communities receive justice

• whether Nigeria remains a leader on the continent or falls behind

Let us choose wisdom over inertia. Empowerment over exploitation.

Let us choose a future where legal training lifts the next generation, not crushes it.

Because justice begins with how we train its defenders.