JudeEsq

Mercy killing, also known as euthanasia, presents one of the most complex moral and legal dilemmas in contemporary society. It raises questions about human suffering, moral responsibility, and the limits of legal authority. In Nigeria, these questions are further complicated by the intertwining influence of law, religion, and cultural values. This article seeks to explore the issue of mercy killing from multiple perspectives, drawing on Nigerian legal principles, Christian ethical thought, and social insights collected from a recent social check conducted to understand how Nigerians perceive this issue in private.

Understanding Mercy Killing

Mercy killing can be defined as the intentional ending of a life to relieve extreme suffering. It is distinct from ordinary homicide in that it is motivated by compassion rather than malice. Philosophically, it raises a central question: is it morally permissible to end a life in order to prevent prolonged suffering, even if it violates established laws or religious teachings? The answer depends on the way the issue is considered.

In Nigeria, as in many other countries, mercy killing is legally classified as murder. The Nigerian Criminal Code and Penal Code provide strict prohibitions against the unlawful taking of human life. There are no legal provisions explicitly allowing euthanasia, whether voluntary or involuntary. Consequently, any act of mercy killing is subject to criminal prosecution. The courts have consistently held that the intentional ending of life, even with consent or compassionate motives, falls within the definition of murder under Nigerian law.

Nigerian Legal Principles on Murder

The Nigerian Criminal Code, which applies primarily in southern Nigeria, defines murder as the unlawful killing of a person with intent or knowledge that the act could result in death. Similarly, the Penal Code, which applies mainly in northern Nigeria, criminalizes intentional homicide. The law does not differentiate between murder motivated by greed, revenge, or compassion. This legal stance reflects the view that human life is inviolable and that no individual has the authority to decide when another person should die.

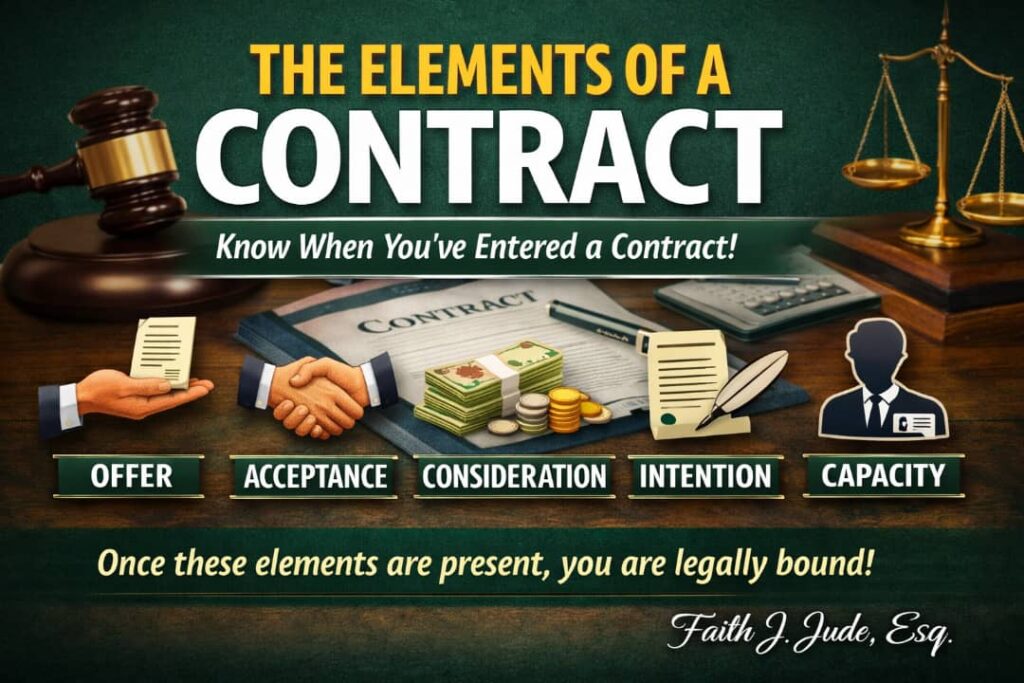

Several legal ideas are relevant in understanding mercy killing in Nigeria. First, the doctrine of mens rea, or criminal intent, requires that a person act with knowledge or intention that their act could result in death. In the case of mercy killing, the actor clearly intends the death, even if the motive is compassion. Second, the law emphasizes the sanctity of life. Courts in Nigeria have often referenced the principle that human life is sacred and must be protected at all costs. Third, there is the idea of legal equality, which implies that all individuals, regardless of suffering, have the same legal protections.

It is worth noting that attempts to justify mercy killing under the Nigerian law are generally unsuccessful. Courts have rejected defences based on compassion, necessity, or consent, arguing that these motivations cannot override the clear statutory prohibition against killing. Therefore, from a purely legal perspective, mercy killing is both impermissible and punishable.

Christian Ethical Perspective

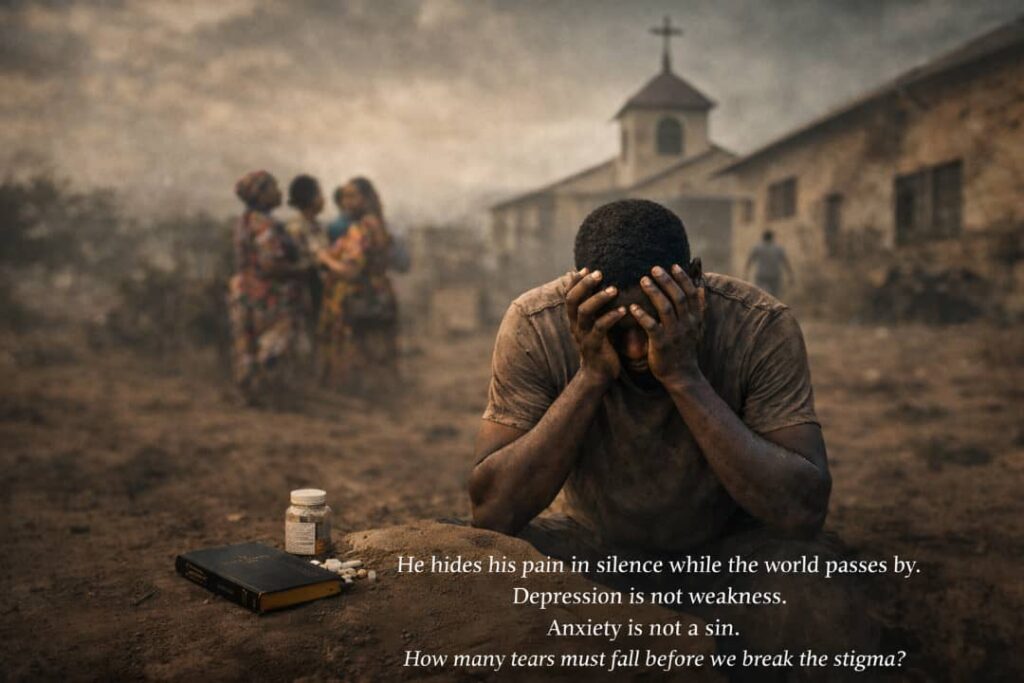

Christianity, which is the dominant religion in southern Nigeria and widely practiced across the country, also condemns the intentional ending of human life. The Bible consistently teaches the sanctity of life, with passages emphasizing that life is a gift from God and that only God has authority over death. For instance, the book of Exodus commands, “Thou shalt not kill,” which has been interpreted by Christian scholars as covering all forms of intentional homicide, including acts motivated by mercy.

However, Christian ethics also values compassion, love, and the relief of suffering. This creates a moral tension. On one hand, ending a life intentionally appears to violate divine law. On the other hand, allowing a person to endure unbearable pain may seem morally cruel. Christian scholars have debated this tension extensively. Some argue that palliative care and spiritual support are the only morally acceptable ways to relieve suffering. Others suggest that, in extreme circumstances, morally ambiguous actions, while still wrong, may be understood in the context of human frailty and love for the suffering.

In practice, this tension influences how Nigerians perceive mercy killing. Many Christians may condemn it legally and doctrinally, yet privately empathize with the decision to end unbearable suffering. This difference between public morality and private feeling is central to understanding social attitudes toward euthanasia.

Insights from Social Check

To understand how Nigerians privately perceive mercy killing, a social check was conducted where participants were invited to share their honest opinions on the topic. The discussions were set up to prevent social pressure, encouraging rational and clear reflections.

One recurring theme was the tension between law and morality. Many participants recognized that legally, mercy killing is murder. Yet, morally, they struggled to categorically condemn it. One participant reflected, “If my child was suffering unbearably and begged me to help her end the pain, I might do it. I would still be breaking the law, but my conscience would understand the act.”

Several participants shared personal stories that illustrate this tension. A woman recounted caring for her terminally ill father. She described witnessing his gradual deterioration, immense suffering, and repeated pleas for relief. She admitted that, while she would never break the law, she secretly understood the reasoning behind mercy killing: “I cannot imagine leaving him to die slowly in agony. The law is clear, but my heart aches for him.”

Others offered more philosophical perspectives. A male participant with a background in medicine argued that if medical technology could end suffering instantly and painlessly, refusing such intervention could itself be a moral failing. Another participant drew on Christian teaching, suggesting that compassion could coexist with wrongdoing: “Helping someone in extreme suffering may be morally wrong in the eyes of God, but it could still be an act of love.”

Interestingly, some participants described the act as akin to a “fictional movie.” They noted that while morally complex, it is not a scenario they expect to encounter personally. These reflections highlight how private moral reasoning can differ from public legal and religious norms.

Comparison with Other Countries

Globally, countries have taken varied approaches to mercy killing. In the Netherlands, Belgium, and Canada, euthanasia is legal under strict conditions, emphasizing patient consent and terminal illness. These countries often require medical oversight and safeguards to ensure that the decision is voluntary and well-considered. By contrast, Nigeria maintains a strict prohibition, prioritizing the protection of life over individual choice. This shows how culture, religion, and law shape attitudes toward the issue.

From a moral standpoint, philosophers have debated whether mercy killing is a compassionate act or an ethical violation. Utilitarian views argue that reducing overall suffering can justify euthanasia. Moral rules, often aligned with Christian teaching, maintain that actions violating duties, such as taking life, cannot be justified even by compassion. The Nigerian context reflects a stronger alignment with moral rules, given the influence of law and religion.

Legal Consequences for Nigerians

Given the current legal rules, anyone engaging in mercy killing in Nigeria risks prosecution for murder. Penalties can include life imprisonment or, in extreme cases, capital punishment under certain interpretations of the law. Legal experts emphasize that, while moral reasoning may offer some understanding, it cannot reduce criminal liability. Families facing terminal illness must therefore rely on palliative care, pain management, and spiritual support within the legal and medical system.

Health professionals in Nigeria face special challenges. They are bound by ethical codes to preserve life while also relieving suffering. Decisions regarding pain management, withdrawal of life support, or refusal of extreme measures must carefully balance compassion and legal compliance. This shows the need for clear guidance and public education on end-of-life care.

Moral Reflections

The Nigerian social check reveals that private morality often differs from public law. While most participants acknowledged the illegality of mercy killing, many expressed empathy for individuals facing unbearable suffering. Some highlighted the importance of intention: ending a life to relieve pain is not the same as murder for greed or revenge. Others stressed the significance of context, suggesting that extreme suffering can make the act morally complicated.

This difference has practical importance. It suggests a gap between law, religion, and human experience. Nigerians may publicly condemn mercy killing while privately understanding or even supporting it under extreme circumstances. This insight is critical for religious leaders, legal experts, and social scholars. It emphasizes the need for discussion, ethical guidance, and better palliative care.

Stories of Compassion and Pain

Several personal stories illustrate the complexity of the issue. One participant shared a story of caring for an elderly uncle who was suffering from advanced kidney disease. His pain was intense, and he often pleaded for relief. The family tried all medical options, but nothing eased his suffering completely. The participant reflected on how difficult it was to watch someone endure such constant pain and admitted that, while he would never break the law, he could understand why some might consider ending the suffering under extreme circumstances.

Another participant spoke of witnessing the suffering of elderly relatives with degenerative illnesses. He expressed that, while he would never commit mercy killing, he understood the impulse and secretly sympathized with those who might consider it. The emotional weight of watching prolonged suffering shapes private morality, creating situations where empathy clashes with formal law.

These stories highlight the complexity of mercy killing in the Nigerian context. They reveal a tension between legal rules, religious teachings, and moral thinking. Compassion, love, and empathy emerge as central factors influencing private attitudes, even when law and religious norms forbid the act.

Conclusion

Mercy killing in Nigeria presents an unresolved moral and legal dilemma. Legally, it is clearly classified as murder. Christian teaching reinforces the sanctity of life, emphasizing that only God has authority over death. Yet, private social reflections reveal deep moral uncertainty. Nigerians can recognize the illegality of the act and empathize with its motivations at the same time.

The insights collected from the social check show that morality is not always aligned with law. Compassion, intention, and context play important roles in shaping private judgments. While Nigerian law maintains a strict prohibition against euthanasia, understanding private perspectives can inform discussions on palliative care, ethical guidance, and societal values.

In the end, mercy killing forces society to confront human suffering, the limits of legal authority, and the role of compassion in moral decisions. Nigerians, like people everywhere, struggle with these questions in private, showing how complex and human these issues truly are. The task for leaders, policymakers, and religious guides is to acknowledge these tensions, provide guidance, and ensure that those facing unbearable suffering receive support that is legal, moral, and humane.