JudeEsq

Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s.

Introduction

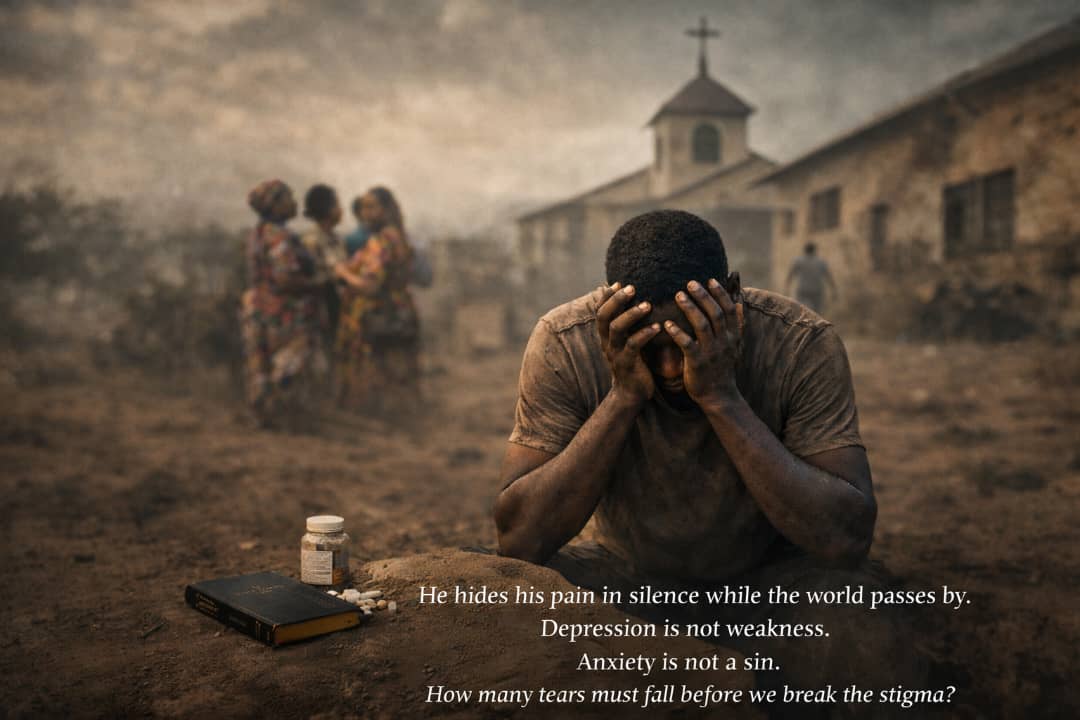

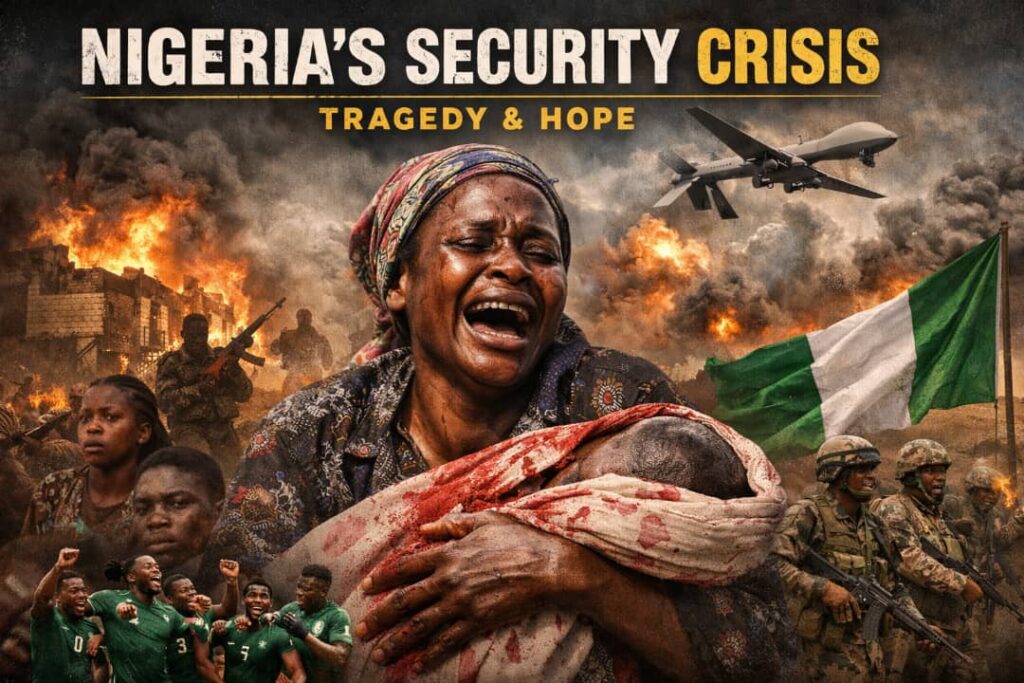

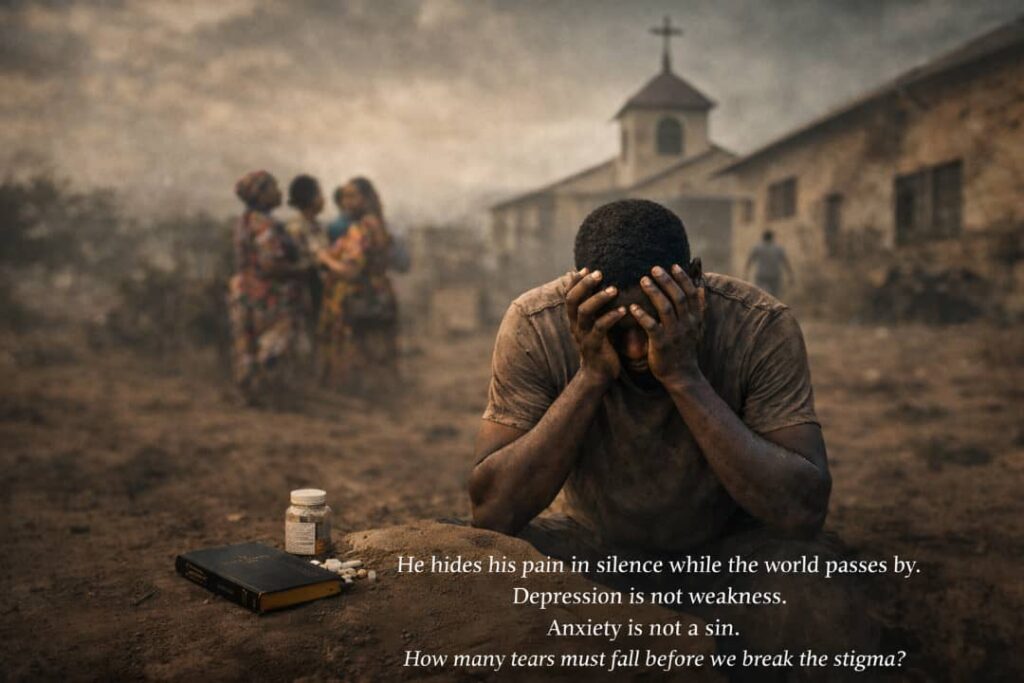

Mental health is one of the most neglected aspects of healthcare in Nigeria. Conditions such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation affect millions of Nigerians every year. Yet, despite their prevalence, mental health issues remain deeply misunderstood, stigmatized, and often dismissed as a personal weakness, spiritual failure, or moral deficiency.

This neglect is compounded by cultural, social, and religious beliefs. In many Nigerian families, discussing emotional distress is considered taboo. Society often labels those with mental health challenges as unreliable, cursed, or spiritually compromised. Even within religious communities, mental illness is frequently interpreted through the lens of faith, with prayers and deliverance sometimes offered as a substitute for professional treatment.

This article seeks to explore mental health stigma in Nigeria from multiple perspectives. We examine the legal framework that governs mental healthcare, Christian ethical and theological perspectives on mental suffering, and insights from a recent confidential survey conducted to understand how Nigerians perceive and respond to mental health issues in private.

Understanding Mental Health Stigma

Stigma is a social process that devalues individuals based on perceived differences from societal norms. Mental health stigma manifests in three main forms:

- Public Stigma: Negative attitudes, discrimination, and social rejection of individuals with mental illness. Examples include exclusion from social gatherings, ridicule, or assumptions of incompetence.

- Self-Stigma: Internalization of societal prejudice, leading individuals to feel shame, guilt, or low self-worth. Many sufferers avoid seeking help due to fear of judgment.

- Institutional Stigma: Policies, laws, or practices that disadvantage individuals with mental health challenges. This includes underfunding of mental health facilities, lack of insurance coverage, or limited professional support.

In Nigeria, stigma is amplified by cultural narratives that associate mental illness with supernatural causes. Families may seek the intervention of spiritual leaders, sometimes delaying medical attention. This intersection of culture, religion, and ignorance creates barriers to effective care and worsens suffering.

Nigerian Legal Context

Nigeria has legal frameworks that recognize mental health but are limited in enforcement and public awareness. The primary law governing mental health is the National Mental Health Act of 2023, which replaced the outdated Lunacy Act of 1958. The 2019 Act was designed to improve access to care, protect patient rights, and reduce discrimination. Key provisions include:

- Right to treatment: Individuals with mental disorders have the right to receive adequate treatment in a safe and humane environment.

- Consent and autonomy: Patients are entitled to participate in decisions regarding their care unless they are deemed incapable of making informed decisions.

- Protection from abuse and discrimination: It is illegal to deny employment, education, or access to services based solely on mental health status.

Despite the law, enforcement remains a challenge. Many Nigerians are unaware of their rights, and public institutions often lack the resources or expertise to implement the provisions fully. Consequently, legal protections often exist only on paper, leaving sufferers vulnerable to neglect, abuse, and social marginalization.

Criminal law intersects with mental health in cases involving suicide and self-harm. Under the Nigerian Criminal Code, attempted suicide is technically illegal, carrying potential fines or imprisonment. This law is rarely enforced in practice, but its existence contributes to stigma, as families and communities may treat suicidal behaviour as a moral or legal failing rather than a medical emergency.

Christian Ethical Perspective

Christianity, the dominant religion in southern Nigeria and widely practiced across the country, provides another lens through which mental health is interpreted. The Bible teaches that life is sacred, human suffering has meaning, and compassion is a moral obligation. Yet, cultural interpretations of Christianity often frame mental illness in spiritual terms, leading to tension between faith and medicine.

Several themes emerge in Christian thought regarding mental health:

- Spiritual causes: Mental illness may be seen as the result of sin, demonic influence, or lack of faith. Individuals struggling with depression or anxiety may be encouraged to pray, attend deliverance sessions, or undergo spiritual cleansing. While these practices can provide comfort and social support, they are not a substitute for medical intervention.

- Moral responsibility: Some Christians believe that suffering should be endured patiently as a test of faith. This belief can lead to moral judgement against those seeking psychological help or expressing distress.

- Compassion and care: The New Testament emphasizes care for the vulnerable, including the sick, downtrodden, and suffering. Ethical teaching supports providing emotional support, counselling, and humane treatment for mental health patients. This creates a moral imperative for churches, families, and communities to support sufferers rather than stigmatize them.

The tension between spiritual interpretations of mental illness and medical understanding contributes to stigma. While faith communities can be a source of comfort and social cohesion, they can also unintentionally perpetuate misunderstanding and shame.

Insights from Social Check

A confidential social check was conducted to understand how Nigerians perceive mental health in private. Participants were asked about personal experiences with depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, or other mental health challenges. Several important patterns emerged:

Societal Pressure

Many participants reported that society often views mental illness as a weakness. One participant shared:

“When I told my family I was seeing a psychologist, they said I was lazy and not praying enough. I felt ashamed and stopped talking about it for months.”

Another noted:

“People joke about depression like it is not real. They say ‘snap out of it’ or ‘just be strong.’ It makes you feel invisible and misunderstood.”

Family Responses

Families can be both supportive and harmful. A female participant recounted caring for her younger brother who had anxiety:

“At first, we thought he was just being dramatic. When he had panic attacks, my parents prayed for him, but no one took him to a doctor. It took months before he got professional help, and even now, some family members call him weak.”

This demonstrates that lack of understanding within families often delays proper intervention and reinforces stigma.

Religious Influence

Several participants described church responses to mental health:

“In my church, people believe depression is a lack of faith. Pastors tell you to pray harder or attend deliverance. Sometimes it helps, sometimes it makes you feel guilty for being sick.”

This illustrates the dual role of religion as a source of comfort and a source of moral pressure, which can intensify shame.

Personal Reflections

A male participant shared a candid reflection on suicidal thoughts:

“I never told anyone. I was afraid they would call me sinful or possessed. I learned to hide it and act normal. Even my closest friends did not know. It is lonely and exhausting.”

Another participant emphasized the importance of empathy:

“I think people with depression are fighting battles we cannot see. Judgement only adds to their burden. Compassion, even small gestures, can make a huge difference.”

Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s.

Medical and Professional Perspectives on Mental Health in Nigeria

Mental health professionals in Nigeria operate within a difficult system. Psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and social workers are few in number compared to the population they serve. According to available medical data, Nigeria has fewer than five hundred practicing psychiatrists for a population exceeding two hundred million people. This shortage means that many individuals with mental health conditions never receive professional care.

Most psychiatric facilities are located in urban centres, leaving rural populations with little or no access to mental healthcare. Where facilities exist, they are often underfunded, understaffed, and poorly equipped. This institutional neglect reinforces stigma. When mental health services appear scarce or hidden away, society learns to see mental illness as something abnormal, shameful, or dangerous.

Mental health professionals interviewed indirectly through the survey responses described frustration with public attitudes. One respondent, who identified as a healthcare worker, explained:

“Many families bring patients only when the condition has worsened. They first try prayers, fasting, traditional healers, and isolation. By the time they come to the hospital, the illness has become severe.”

Another medical professional noted that stigma does not only affect patients, but also caregivers:

“Families feel embarrassed. They hide relatives with mental illness. Some abandon them completely. It is painful to see.”

Medical understanding of mental health treats conditions such as depression and anxiety as illnesses involving biological, psychological, and social factors. They are not signs of weakness, laziness, or spiritual failure. Treatment often involves therapy, medication, lifestyle changes, and strong social support. When stigma delays care, recovery becomes more difficult.

Suicide and the Law in Nigeria

Suicide remains one of the most misunderstood mental health issues in Nigeria. While global health bodies recognize suicide as a public health concern linked to mental illness, Nigerian law still treats attempted suicide as a criminal offence.

Under sections of the Criminal Code applicable in southern Nigeria, attempted suicide can attract fines or imprisonment. In northern Nigeria, under the Penal Code, attempted suicide is also criminalized. Although prosecutions are rare, the existence of these laws sends a powerful message. It frames suicidal behaviour as a crime rather than a medical emergency.

Participants in the social check repeatedly mentioned fear of legal trouble as a reason people do not seek help. One participant stated:

“People are scared. If you tell someone you want to kill yourself, they might call the police instead of helping you.”

Another added:

“It makes families hide it. They do not want shame or police involvement.”

Legal scholars have argued that criminalizing attempted suicide worsens stigma and discourages intervention. Instead of seeking help, individuals suffer in silence. Some countries have decriminalized attempted suicide and replaced punishment with mandatory psychiatric evaluation and care. Nigeria has not yet taken this step, and this legal position continues to influence social attitudes.

Family Dynamics and Cultural Expectations

In Nigerian society, family plays a central role in shaping identity, behaviour, and values. While this strong family structure can provide support, it can also intensify stigma when mental illness is involved.

Many families expect emotional strength, resilience, and endurance, especially from men. Depression and anxiety are often dismissed as excuses or character flaws. A male participant shared:

“As a man, you are expected to be strong. When I said I was tired mentally, my uncle told me to go and hustle harder.”

Women face a different kind of pressure. Emotional distress may be dismissed as drama, hormones, or spiritual attack. One female participant said:

“They told me it was because I was not married yet. That I was overthinking.”

Family reputation is another major factor. Mental illness is sometimes seen as a stain on the family name. Parents fear that admitting a child has a mental health condition could affect marriage prospects or social standing. As a result, families may hide the issue, deny treatment, or isolate the individual.

In extreme cases, individuals are restrained, locked away, or taken to unregulated spiritual centres where abuse may occur. These practices are often justified as discipline or spiritual correction but amount to human rights violations.

Religion as Comfort and Conflict

Christianity plays a powerful role in Nigerian life. Churches are places of hope, healing, and community. For many people with mental health challenges, faith provides comfort, meaning, and resilience. Prayer, fellowship, and belief can reduce loneliness and despair.

However, religion can also deepen stigma when mental illness is framed as purely spiritual. Several participants described being told their depression was caused by sin, demonic attack, or lack of faith. One participant shared:

“They told me to repent. I was already struggling. That made it worse.”

Another said:

“I felt guilty for taking medication. I thought it meant I did not trust God.”

This creates an internal conflict for believers. They may feel torn between seeking medical help and remaining faithful. Some stop treatment to avoid judgment, while others hide their condition from church members.

Christian ethical teaching, when properly understood, does not support neglect or shame. The Christian duty of love, compassion, and care for the suffering calls for understanding mental illness as part of human vulnerability. Faith and medicine need not be in opposition. Many participants expressed hope for better education within churches.

Personal Stories from the Social Check

The most powerful insights from the social check came from personal stories. These stories reveal the emotional cost of stigma and silence.

One participant shared a story of a close friend:

“My friend was always quiet. Nobody noticed. One day, he was gone. People said he was weak. They never asked why he was hurting.”

Another participant spoke about recovery:

“I finally got help. Therapy saved my life. But I had to do it quietly. Even now, only two people know.”

A woman described supporting her sister:

“My sister had postpartum depression. Our family said she was ungrateful. I stayed with her. I listened. Slowly, she healed.”

These stories highlight a common pattern. Silence. Judgment. Fear. But also resilience, empathy, and quiet courage.

Public Perception and Media Influence

Nigerian media often reinforces stereotypes about mental illness. News reports frequently link mental illness with violence or crime. Movies portray mentally ill characters as dangerous or ridiculous. Social media jokes trivialize depression and suicide.

Participants noted that these portrayals shape public perception. One said:

“When people hear mental illness, they think of madness. They do not think of sadness or fear.”

Changing public perception requires responsible media representation. Stories of recovery, empathy, and normalcy can help reduce fear and stigma.

Ethical Reflections

Mental health stigma raises serious ethical questions. Is it right to shame someone for an illness they did not choose? Is silence a form of harm? Do cultural values justify neglect?

From a moral standpoint, society has a duty to protect vulnerable individuals. Compassion requires listening, not judging. Ethics demands that suffering be addressed, not dismissed.

The social check revealed that many Nigerians privately understand this, even if public attitudes remain harsh. People expressed empathy when speaking confidentially. This suggests that stigma is maintained not only by belief, but by fear of social consequences.

Recommendations for Change

Reducing mental health stigma in Nigeria requires effort at multiple levels.

First, legal reform is needed. Decriminalizing attempted suicide would reduce fear and encourage help seeking.

Second, public education must improve. Mental health literacy should be included in schools, churches, and community programs.

Third, religious leaders should receive training on mental health. Churches can become safe spaces rather than sources of shame.

Fourth, families must learn to listen without judgment. Support saves lives.

Finally, individuals must speak openly when safe to do so. Silence protects stigma. Honest conversation weakens it.

Conclusion

Mental health stigma in Nigeria is deeply rooted in law, culture, family, and religion. Depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts are real experiences that affect real people. The legal system, while improving, still carries harmful remnants that reinforce shame. Religious interpretations, when misunderstood, can deepen guilt rather than offer healing.

The social check revealed a hidden truth. Behind public silence lies private pain, empathy, and understanding. Nigerians are thinking about these issues, even if they do not say so openly.

Addressing mental health stigma requires courage. Courage to reform laws. Courage to educate. Courage to listen. And courage to care.

Mental illness is not a moral failure. It is a human experience. How society responds to it reveals its true values.