JudeEsq

Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s.

How Child Labour Has Changed Form: From Physical Labour to Internet Labour

Child labour has always been a social problem. For centuries, children were employed in factories, fields, and workshops, performing physically demanding and often dangerous tasks. The consequences were clear: stunted growth, illness, injury, and lifelong deprivation. Laws, regulations, and international conventions gradually reduced the prevalence of traditional child labour, recognising the importance of childhood, education, and physical well-being.

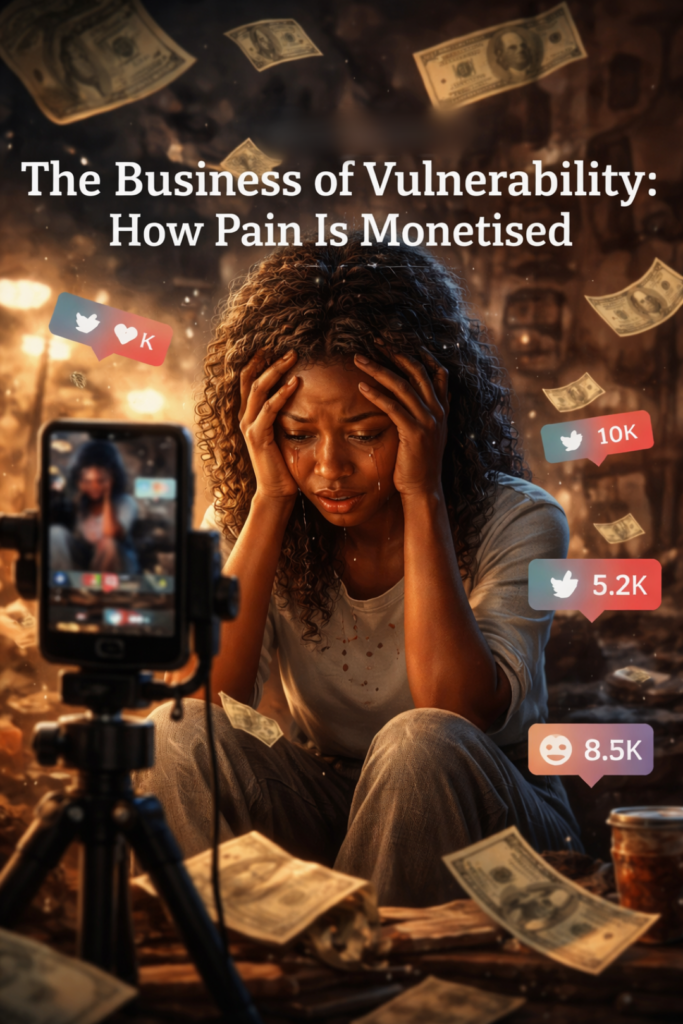

Yet, in the 21st century, child labour has not disappeared. It has transformed. It has migrated from the streets and factories into a space few imagined decades ago: the internet. Children are now exploited not for physical output alone, but as digital commodities. Their faces, voices, and personalities are monetised, their identities turned into content for advertising, entertainment, and personal branding. This shift represents a new form of child labour: internet labour.

Parents, whether consciously or unconsciously, have become managers, agents, and directors of their children’s online presence. Some begin even before birth, documenting pregnancies, posting ultrasound images, and creating social media narratives about unborn children. From the womb, a digital identity is being crafted, measured by likes, shares, and views. Birth becomes a launch point, and infancy becomes a career. Playtime, schooling, and basic privacy are secondary to content creation and online engagement.

While these posts may seem harmless or even affectionate to viewers, the children involved are being positioned as commodities. Every smiling face, every tantrum, every awkward milestone is captured, edited, and broadcast. Algorithms reward extremes: moments of humour, embarrassment, or vulnerability generate engagement and revenue. Over time, the child’s life is no longer lived for themselves but curated for the consumption of strangers.

This transformation carries profound implications. Unlike traditional labour, which impacted the child physically, internet labour impacts psychological and emotional development. The digital footprint created in childhood is permanent. Embarrassing videos, awkward behaviour, and intimate family moments can persist online indefinitely. Children, once old enough to comprehend the permanence of these records, often experience shame, regret, and humiliation. Their own childhood becomes a source of stress rather than a space of safety and growth.

Psychological studies suggest that prolonged exposure to public scrutiny, humiliation, and lack of agency over one’s personal narrative can increase the risk of mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, and in extreme cases, suicidal ideation. The online child labour phenomenon may therefore have a delayed but serious impact: a generation of adults looking back at their own digitally commodified childhoods, burdened by regret, embarrassment, and a sense of lost autonomy.

The nature of internet labour encourages performance pressure. Children learn to anticipate the gaze of others, measure their value in likes, and conform to online expectations from an age when they cannot make informed choices. This undermines natural development, erodes self-esteem, and teaches children to externalise their self-worth. Unlike factory labour, where physical injury is immediate and visible, internet labour produces harm that is cognitive, emotional, and enduring.

There is a legal and ethical challenge. Current child labour laws, even in jurisdictions with strict protections, often fail to encompass online exploitation. Platforms, content monetisation structures, and parental controls create an environment where the child is legally present but unprotected, socially exploited but ostensibly consented to by guardians. The law lags behind technology, and the consequences may only become visible years later, when children are adults grappling with the fallout of their early digital exposure.

Regulation, Ethics, and the Long-Term Consequences of Internet Labour

The rapid rise of internet labour has exposed a critical gap between technology, social norms, and legal protections. In many countries, child labour laws were designed to regulate factories, farms, and workplaces. These laws focus on physical safety, working hours, and education. They did not anticipate the world of YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and other digital platforms, where children’s content can be monetised by parents, advertisers, or third-party agencies.

Globally, responses have been inconsistent. Some countries, like the United States, have implemented child performer laws that apply to traditional media, but these often fail to account for content produced by parents at home. The European Union has begun exploring digital protections for children, focusing on consent, privacy, and online profiling, but enforcement remains difficult. In much of the world, the child in front of the camera is treated as a participant in family life rather than a worker, even when their image generates substantial income.

This regulatory lag creates a moral and social dilemma. Parents may view internet labour as harmless or even beneficial. It provides financial opportunities and can build social capital. Yet the child’s autonomy is compromised. Every uploaded image, video, or story shapes a digital identity over which they have no control. The question becomes not whether the activity is profitable, but whether the child is allowed to be a child.

Psychologists warn that constant exposure to performance expectations from infancy can produce long-term harm. Children internalise the need for approval and recognition, developing self-worth that depends on the responses of strangers rather than family or peers. Public humiliation or simple embarrassment in a viral video can leave a permanent psychological scar. The shame associated with their own childhood may emerge during adolescence or adulthood, sometimes triggering severe anxiety, depression, and in extreme cases, suicidal thoughts.

A particularly alarming aspect of this new form of labour is permanence. Unlike physical work, which leaves its mark temporarily, digital content persists indefinitely. Videos, photos, and posts can be downloaded, shared, and resurface years later. Children grow up knowing that mistakes, tantrums, or private family moments exist online for the world to judge. This permanent exposure can distort memory and self-perception, making childhood a source of trauma rather than a safe developmental period.

Ethically, the responsibility lies both with parents and platforms. Parents must understand that consent from a minor is impossible in any meaningful sense. A newborn or toddler cannot weigh the consequences of online exposure, nor can they refuse participation. Platforms, in turn, have a duty to recognise the risks inherent in monetised child content. Algorithms prioritise engagement, not well-being. Viral content that exploits vulnerability often receives rewards, creating a systemic incentive for further exploitation.

The long-term societal consequences are profound. If a generation grows up constantly measured, recorded, and judged, the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and self-harm may rise. Children may enter adulthood burdened by digital histories they cannot erase, facing social stigma and internalised shame. The idea of childhood as a protected, exploratory period may disappear for some, replaced by a culture of performance and exposure from the womb onward.

Confronting this problem requires a combination of regulation, parental education, and platform responsibility. Governments must extend child labour protections to online activities, including content creation for profit. Parents must prioritise their child’s privacy, autonomy, and well-being over monetisation. Platforms must adopt stricter verification, consent mechanisms, and content review practices that protect minors from exploitation. Only through coordinated action can the physical, psychological, and social harm of modern child labour be mitigated.

Psychological and Societal Consequences of Digital Child Labour

The shift from physical labour to digital labour does not reduce harm. It transforms it. Where once a child might suffer injury, fatigue, or malnutrition, they now face psychological and emotional burdens that are invisible but enduring. These burdens are compounded by permanence. Unlike a factory accident, which is confined in time, online content lasts indefinitely. The child cannot escape it, rewind it, or delete it from memory, even if the original post is removed. Copies remain circulating, archives exist, and search engines remember.

Children who grow up as online performers learn early to perform not for themselves but for others. Their value becomes linked to external validation. Each smile, laugh, tantrum, or misstep is measured in views, likes, or comments. Mistakes are not private lessons but public records. The constant pressure to perform can induce anxiety, stress, and perfectionism. When children fail to meet expectations, they often internalise blame, believing that inadequacy is a personal failure rather than a structural consequence of exposure and exploitation.

As these children enter adolescence, a new set of challenges emerges. They gain the cognitive capacity to understand the permanence of their digital footprint. Videos of childhood tantrums, unflattering moments, or intimate family interactions may resurface at school, among peers, or in public spaces. Adolescents are highly sensitive to peer perception, and exposure of personal vulnerability can be devastating. Research indicates that public shaming in adolescence correlates strongly with depression, social withdrawal, and suicidal ideation.

Even if children feel pride in their early accomplishments or enjoy attention as a form of validation, the long-term consequences are often harmful. Regret and embarrassment can accumulate. A playful video posted at age four can become a source of torment at age fifteen. Digital content that parents believed was innocent can later be interpreted by the child as exploitation or violation of privacy. This cumulative shame can contribute to long-term identity conflicts, decreased self-esteem, and chronic stress.

Societally, the consequences are equally alarming. A generation raised as digital commodities may develop distorted social norms, where privacy is undervalued, and performance for external approval becomes standard. Children may struggle to form authentic relationships, constantly measuring themselves against public perception. They may also feel pressure to continue the pattern into adulthood, monetising their own lives and reproducing the cycle of exposure for the next generation.

Mental health professionals warn that this phenomenon may contribute to a rise in suicide rates among those who experienced intensive digital exposure in childhood. Adolescents and young adults may feel trapped by their digital past, unable to escape the scrutiny of their early years. The constant comparison with curated online identities can exacerbate feelings of inadequacy, shame, and hopelessness. In some cases, the inability to control the narrative of one’s own life can become unbearable.

Preventing these outcomes requires immediate attention. Parents must recognise that children cannot consent to digital exposure, no matter how appealing monetisation, fame, or social approval may seem. Platforms must implement stronger protective measures, prioritising child welfare over engagement metrics. Policymakers must expand existing child protection laws to account for online labour, recognising psychological harm as a legitimate form of exploitation.

The transformation of child labour into digital labour is not merely a technological phenomenon. It is a psychosocial crisis. A society that permits children to be commodified online, from birth through adolescence, risks creating a generation burdened with regret, shame, and mental health challenges that may persist throughout life. Without urgent intervention, the cost of digital childhood exploitation will be measured not in likes or revenue, but in lives disrupted and futures diminished.

This Is Different From Being A Child Actor

A child appearing in a movie role and a child being used for internet content are not the same, even though both involve a child being seen by the public.

A child actor in a movie operates within a defined, time limited, and regulated structure. The role has a script, a clear beginning and end, professional supervision, and in many jurisdictions, legal safeguards. There are limits on working hours, requirements for schooling, guardianship rules, and often financial protections so the child’s earnings are preserved. Most importantly, the child is portraying a character, not exposing their real private life. The embarrassment, vulnerability, or actions belong to a fictional role, not the child’s personal identity.

By contrast, a child used for internet content is often working continuously without structure or protection, here, the child’s entire life becomes a reality show. There is no script, no end date, and no clear separation between the child’s real life and the content. Their real emotions, tantrums, fears, mistakes, and private moments are the product. There is usually no legal monitoring, no guaranteed protection of earnings, and no meaningful consent. The content follows the child forever because it is not a role. It is their actual life, permanently recorded and searchable.

In simple terms, a movie role is a job with boundaries. Internet child content is a life without privacy turned into labour.

Conclusion

Child labour has changed, but harm has not disappeared. It has simply taken on a new, invisible form. Children are no longer only exploited in factories, fields, or workshops. They are exploited on screens, in living rooms, and on social media platforms. From the womb to adolescence, their lives are captured, shared, and monetised. Their identities become products, and their childhoods become public property.

The consequences of this transformation are profound. Unlike physical labour, which primarily affects the body, internet labour targets the mind, emotions, and sense of self. Children grow up learning to perform for approval, internalising validation from strangers rather than from safe, nurturing environments. Childhood mistakes, private moments, and natural vulnerability are preserved indefinitely, often resurfacing years later to generate embarrassment, shame, and regret.

Psychologists warn that these experiences can have lasting effects. Constant exposure, public scrutiny, and loss of privacy increase the risk of anxiety, depression, and even suicidal thoughts. Children who once performed for likes and views may later confront a digital past they cannot erase, shaping adulthood with feelings of inadequacy, humiliation, and lost autonomy. This is harm that the law, society, and technology have yet to fully address.

The response must be multi-layered:

★ Parents must prioritise the well-being of children over fame, financial gain, or social approval.

★ Digital platforms must implement protections that prevent exploitation, including stronger consent requirements, identity safeguards, and limits on monetisation for content involving minors.

★ Policymakers must expand legal systems to recognise psychological harm as a form of child labour and establish clear accountability for guardians, creators, and platforms.

Society itself has a role:

★ Audiences must resist the urge to consume content that exploits children.

★ Engagement, sharing, and applause for digital childhood exploitation perpetuate the cycle.

★ Recognition of the problem and collective refusal to normalise it can create a culture that respects childhood, privacy, and human dignity.

The evolution of child labour into internet labour is not an inevitable consequence of technology. It is a choice society is making each time a child’s life is monetised for content. If action is not taken, the long-term costs will be measured not in engagement metrics or revenue, but in mental health crises, regret, and the loss of authentic childhoods, even suicide.

Protecting children from digital exploitation is urgent. Childhood must remain a time of growth, exploration, and safety. Lives cannot be content. Childhood cannot be a commodity. Society must choose humanity over virality, and privacy over profit. Only then can children grow free from the psychological scars of a childhood spent performing for the world.