JudeEsq

Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s.

INTRODUCTION:

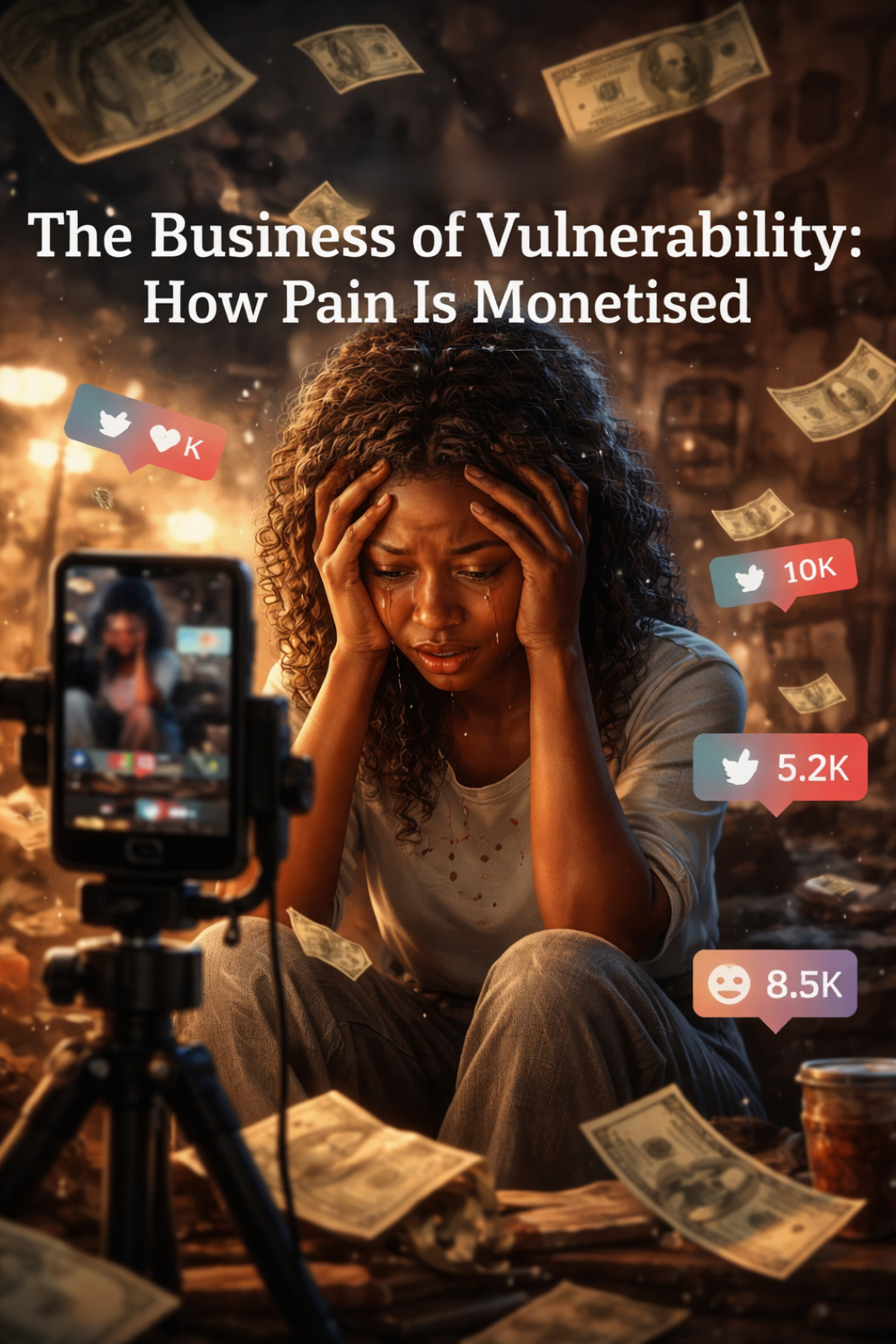

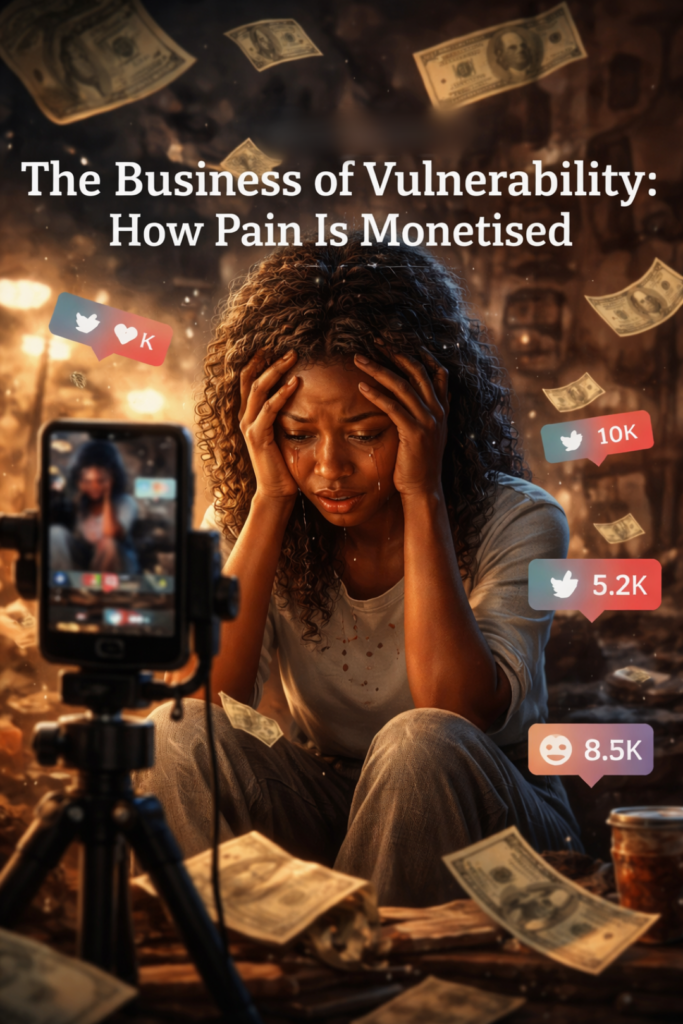

WHEN PAIN BECAME CONTENT

There was a time in Nigeria when suffering was private. When grief was shared quietly among family, neighbours, church members, and friends. When charity was done discreetly, without cameras, without hashtags, without the need for applause. A hungry person was fed and no one announced it. A widow was helped and her name was protected. A struggling mother received aid and went home with her dignity intact. That culture is not ancient history. It lived with us for generations.

Something has changed.

In today’s Nigeria, pain has become currency. Vulnerability has become product. Suffering has become content. The more broken the subject, the higher the engagement. The more exposed the victim, the more profitable the post. This is not an exaggeration. It is a visible social shift driven by social media platforms that reward attention, outrage, pity, and shock with money, followers, influence, and relevance.

What we are witnessing is not kindness. It is the business of vulnerability.

This article examines how pain is monetised in Nigeria, how dignity is stripped in the name of content creation, and how the law responds to these excesses. It does so from the standpoint of Nigerian law, Nigerian social values, and Christian moral teaching on respect, dignity, and silent charity. It is written plainly, because truth does not need decoration.

THE SOCIAL MEDIA ECONOMY AND THE RISE OF HUMAN SPECTACLE

Social media has created a new informal economy in Nigeria. People earn livelihoods from views, likes, shares, subscriptions, and donations. There is nothing illegal about earning money online. There is nothing immoral about content creation. The problem begins when the human person becomes raw material.

In this economy, trauma sells. Tears sell. Shame sells. A man crying publicly will outperform a man speaking calmly. A child in rags will attract more attention than a child whose face is hidden. A corpse will trend faster than a living person asking for help.

Content creators know this. Many admit it privately. Some admit it openly. Algorithms reward extremity. Ordinary kindness does not go viral. Quiet assistance does not pay bills. So suffering is exaggerated, filmed closely, edited dramatically, and uploaded without restraint.

This is where law and morality must speak.

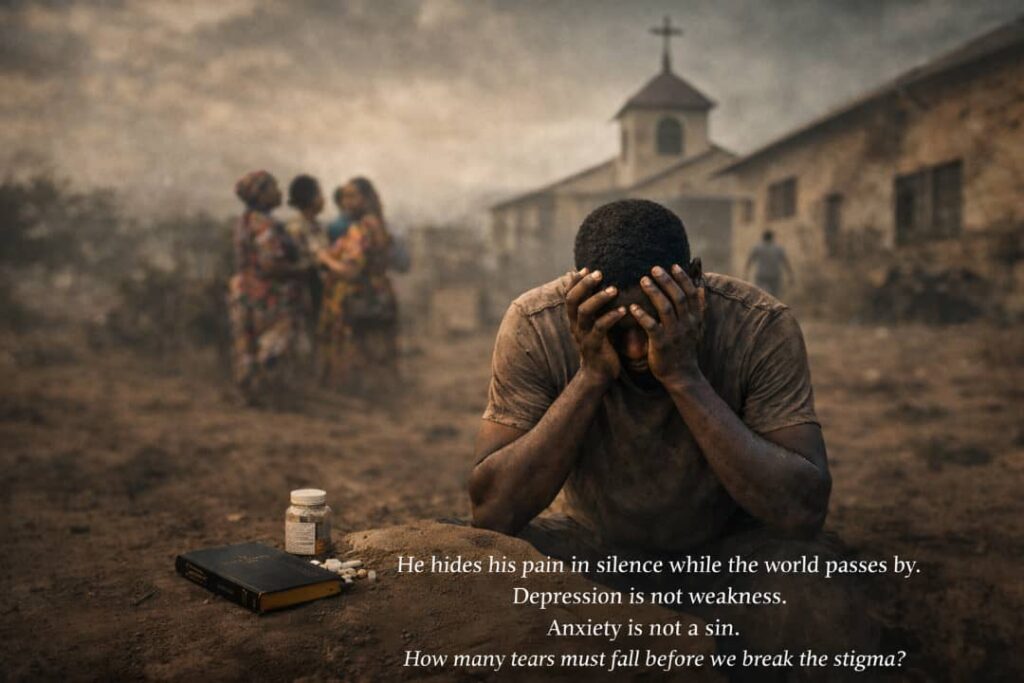

THE CHRISTIAN UNDERSTANDING OF DIGNITY AND SILENT GOOD

Christian teaching, which remains deeply influential in Nigerian society, is clear on human dignity. Every person is created in the image of God. This dignity is not lost because of poverty, age, gender, illness, shame, or circumstance. It is inherent. It cannot be voted away by likes. It cannot be traded for views.

Christ himself warned against publicised charity. He spoke against announcing good deeds with trumpets. He taught that when one gives, the other hand should not know. This was not poetic exaggeration. It was moral instruction. Help should lift people, not expose them. Charity should restore dignity, not auction it.

When a content creator films a struggling person without consent, uploads their face, their home, their pain, and then justifies it by saying they are helping, Christianity does not applaud. It questions motives. It asks who truly benefits. It asks why dignity was the price.

THE LEGAL FOUNDATION OF DIGNITY IN NIGERIA

The Nigerian Constitution is not silent on dignity. Section 34 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria guarantees the right to dignity of the human person. This right is not decorative. It is enforceable. It protects Nigerians from degrading treatment, from humiliation, from being used as objects.

Dignity under Nigerian law is not limited to physical abuse. It includes treatment that strips a person of self worth, that exposes them to public ridicule, that reduces them to a spectacle. Courts have consistently held that dignity is about how a person is treated, not just what is done to their body.

When someone’s worst moment is filmed without consent and broadcast to millions, the question is simple, was their dignity respected?

If the answer is no, then the law has something to say.

THE NORMALISATION OF CONSENT VIOLATIONS

One of the most dangerous developments in Nigeria’s social media culture is the normalisation of filming without consent. Cameras are turned on in markets, hospitals, streets, hotels, schools, and slums without warning. People are recorded while grieving, begging, sleeping, crying, or simply existing.

Consent is dismissed as unnecessary. After all, it is a public place, some say. After all, they are poor, others argue. After all, the creator means well.

None of these excuses stand firmly under Nigerian law.

Consent matters. Especially where the content exposes identity, vulnerability, or sensitive personal circumstances. The law does not permit a free for all simply because a phone has a camera.

THE FIRST SIGNS OF SOCIAL CONSEQUENCE

This social check included informal surveys and interviews conducted among law students, young lawyers, church leaders, content creators, victims, and ordinary Nigerians across Lagos, Abuja, Port Harcourt, Onitsha, Ibadan, and Enugu. The question was simple. How do you feel when you see people’s pain turned into content?

The responses were telling.

A final year law student in Ibadan said she feels angry but helpless. She knows it is wrong but feels society rewards it.

A church worker in Enugu said it breaks his heart. He said help used to be quiet. Now help comes with cameras and commentary.

A content creator in Lagos admitted that videos showing suffering perform better. He said he struggles with guilt but the bills do not care about his conscience.

A young woman who once appeared in a viral charity video said she regrets it deeply. She said people recognise her, mock her, and ask questions she cannot escape.

These are not isolated voices. They represent a growing discomfort that something sacred has been violated.

WHAT THIS ARTICLE WILL DO

This article will not shout. It will explain.

It will examine the legality of filming without consent. It will address pranks, public humiliation, charity content, and post death exposure. It will analyse the consequences under Nigerian criminal law, civil liability, child protection law, and data protection obligations.

It will also confront the excuses. Feeding your family does not cancel another person’s rights. Being a content creator does not suspend the law. Good intentions do not erase harmful outcomes.

Above all, it will insist on one truth:

Your freedom ends where another person’s rights and dignity begins.

CONSENT IS NOT OPTIONAL: WHAT NIGERIAN LAW ACTUALLY SAYS

In Nigeria today, consent has been dangerously misunderstood. Many people speak of it as though it is a foreign idea imported from the internet, something soft, something exaggerated, something that only matters in private spaces. This misunderstanding has caused real harm.

Under Nigerian law, consent is not a social courtesy. It is a legal requirement in many situations, especially where a person’s identity, image, voice, or private circumstances are involved.

The idea that filming someone in distress without permission is acceptable simply because it happens in public is false. Nigerian law does not support that position.

THE RIGHT TO PRIVACY AND IMAGE

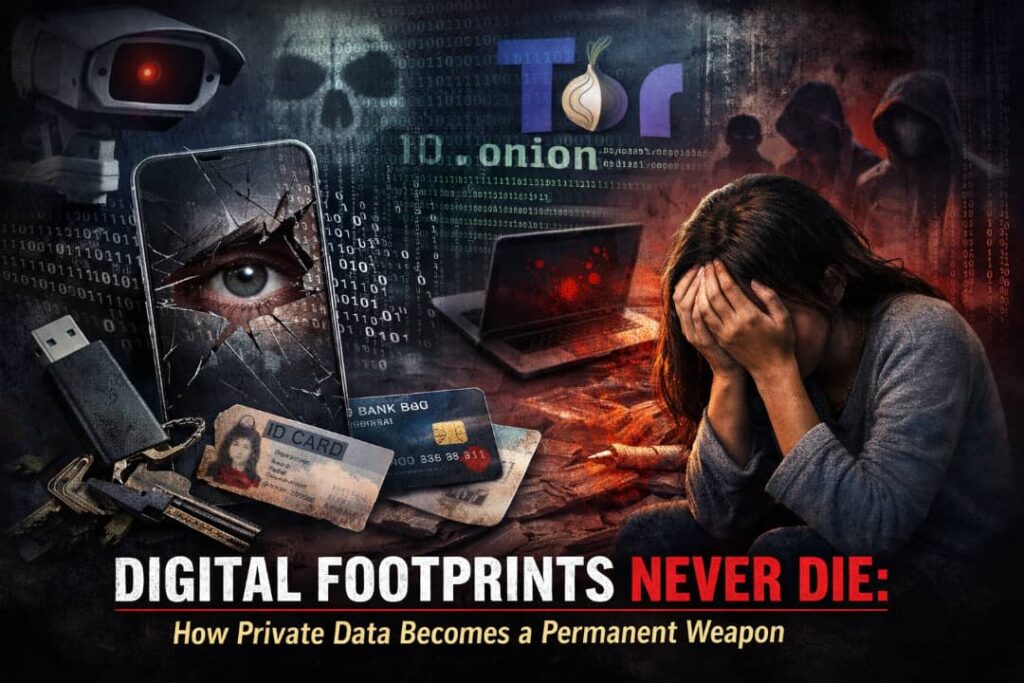

Although the Nigerian Constitution does not expressly list a right to image, the right to privacy under Section 37 is broad. It protects citizens in their homes, correspondence, and private life. Courts have interpreted privacy to include protection from unwanted exposure of personal affairs.

A person does not lose their private life because they step outside. A grieving man in a hotel room, a woman crying in a hospital corridor, a child begging on the street still retains personal dignity and privacy. Recording and publishing such moments without consent intrudes into that private life.

When a video is uploaded online, it is no longer a fleeting observation. It becomes permanent. It can be downloaded, shared, mocked, edited, and weaponised. Nigerian courts increasingly recognise this permanence as a serious harm.

FILMING WITHOUT CONSENT AS A CIVIL WRONG

Beyond constitutional rights, Nigerian tort law provides remedies. Filming and publishing a person’s image without consent in a degrading context can amount to invasion of privacy, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and defamation where reputation is harmed.

A key point often ignored is this: harm does not require bad intention. A creator may believe they are helping. The law looks at effect, not excuse.

If a person is humiliated, exposed, or endangered by content, liability can arise regardless of motive.

CHILDREN AND THE LAW: ZERO TOLERANCE

Where children are involved, Nigerian law is even clearer. The Child Rights Act prioritises the best interest of the child above all other considerations. A child cannot legally consent to exposure that may harm their future.

Filming a minor mother, her children, or any child in a vulnerable situation and broadcasting their faces without protection violates the spirit and letter of child protection laws. Poverty does not cancel childhood. Parenthood does not cancel minority.

Even where assistance is given, it does not justify exposure. The law demands protection, not performance.

DATA PROTECTION AND DIGITAL RESPONSIBILITY

Nigeria’s data protection regime treats images and videos as personal data. Publishing identifiable footage without lawful basis or consent can amount to data misuse. This applies to individuals, not just corporations.

Content creators are not exempt because they are small or informal. The law does not recognise influencer status as immunity.

THE PROBLEM WITH PRANKS

Prank content has become one of the most legally risky forms of entertainment. What begins as laughter often crosses into harassment, intimidation, or public humiliation.

Under Nigerian criminal law, acts that cause fear, distress, or breach of peace can attract liability. A prank that results in panic, injury, or emotional harm is no longer comedy. It becomes an offence.

Courts are not persuaded by laughter added in post production. They examine the lived experience of the victim.

WHEN GOOD INTENTIONS FAIL

Many creators argue that their intentions are good. They claim awareness, charity, or social impact. Nigerian law does not ignore intention, but it does not worship it either.

A well intended act that violates rights is still unlawful. Charity does not grant a licence to expose. Assistance does not authorise humiliation.

Christian ethics reinforces this. If your good deed requires another person’s shame, it is not good.

A VOICE FROM THE SURVEY

A middle aged woman interviewed in Port Harcourt put it simply. She said help that comes with a camera feels like punishment.

A young man in Abuja said he would rather remain hungry than be filmed crying.

A law lecturer in Lagos warned that courts will not remain silent forever. He said society is testing legal patience.

THE LINE THAT MUST NOT BE CROSSED

The law draws a clear line: you may tell stories, you may advocate, you may help. But you must not strip people of dignity to do it.

Your freedom to create content stops where another person’s rights begin. This is not cruelty. It is order.

WHEN EVEN DEATH IS NOT ENOUGH: FILMING THE DEAD AND THE GRIEF STRIPPED BARE

There are lines that societies once understood instinctively. Lines no law needed to draw because conscience already had. One of those lines was death.

In Nigerian culture, death has always been treated with solemn respect. The dead were prepared quietly. Families mourned in privacy. Even enemies lowered their voices in the presence of a corpse. To expose the dead unnecessarily was considered shameful, not brave, not informative, not helpful.

Today, that instinct is fading.

Phones now enter hotel rooms, hospital wards, accident scenes, and mortuaries. Corpses are filmed before families are informed. Grief is broadcast before it is processed. The dead are turned into content while their bodies are still warm.

This is not progress. It is moral collapse.

THE LEGAL STATUS OF THE DEAD UNDER NIGERIAN LAW

Under Nigerian law, the dead are not objects without protection. While a corpse is not a legal person, the law recognises duties owed to it and to the living connected to it.

Improper handling of a corpse, unlawful interference, or indecent treatment can attract criminal liability. The Criminal Code prohibits acts that outrage public decency or offend against morality. Filming a naked or partially exposed corpse and distributing it online can fall squarely within these prohibitions.

Beyond criminal law, the family of the deceased retains enforceable rights. Publishing images of a deceased person in a degrading state can amount to a violation of the family’s right to dignity, privacy, and emotional wellbeing.

The law recognises grief as a protected human experience.

THE HOTEL ROOM VIDEO AND THE QUESTION OF DECENCY

In the last quarter of 2025, the death of a Nigerian comedian sparked public outrage. A friend who was also a content creator recorded a video of the deceased lying lifeless on a hotel bed. The footage circulated rapidly. The deceased was exposed in a manner that nearly revealed private parts.

The legal issue here is not curiosity. It is consent and decency.

A dead person cannot consent. That duty of care shifts to those present and to the family. Recording such footage without lawful authority, without family consent, and without compelling public interest is deeply problematic under Nigerian law.

This was not investigative journalism. It was not evidence gathering for authorities. It was content.

And content has consequences.

HOSPITALS, ACCIDENT SCENES, AND THEFT OF LAST MOMENTS

Hospitals have become stages for viral content. Patients are filmed gasping for breath. Accident victims are recorded bleeding. Family members are captured crying uncontrollably. These videos are uploaded with captions asking for prayers or donations.

But the law asks a harder question. Were these people given a choice?

Hospitals are not entertainment venues. Accident scenes are not film sets. Filming in such spaces without consent can breach hospital regulations, privacy rights, and in some cases obstruct emergency response.

A moment meant for medical care or final words is stolen and sold to the internet.

THE CHRISTIAN VIEW OF DEATH AND GRIEF

Christianity teaches that death is sacred. The body is to be treated with honour. Mourning is to be respected. Christ himself wept privately before raising Lazarus. He did not summon a crowd for spectacle.

Publicising death for profit violates this sacredness. It turns mourning into marketing. It trades reverence for reach.

Helping families through tragedy does not require cameras. Comfort does not require uploads. Compassion does not need proof.

VOICES FROM THE SOCIAL CHECK

A nurse interviewed in Abuja said she has chased content creators out of emergency rooms more times than she can count. She said they hide behind prayerful captions while violating patients.

A father in Benin City said he discovered his son’s accident online before the police contacted him. He said the video haunts him.

A young content creator in Owerri admitted he once filmed an accident victim but deleted it later. He said something felt wrong that analytics could not fix.

WHEN LAW MEETS CONSCIENCE

Many ask whether the law is too harsh when content creators are arrested or sanctioned. They say the creator was only trying to feed his family. They say the punishment is excessive.

But the law is not a charity. It is a boundary.

Freedom without limits becomes violence. Expression without responsibility becomes cruelty. When the dead and the grieving become raw material, society must respond.

Death should be enough to stop the camera. If it is not, then the law must.

POVERTY AS PERFORMANCE AND CHARITY AS CONTENT

There is a particular kind of cruelty that disguises itself as kindness. It smiles. It gives gifts. It records everything. Then it uploads the footage and waits for applause.

In Nigeria’s social media era, poverty has become one of the most profitable genres of content. Slums are filmed like tourist attractions. Hungry families are lined up like exhibits. Children are asked to repeat their stories for better angles. Mothers are told to cry again because the first take was not emotional enough.

This is not assistance. It is performance.

THE MYTH OF JUSTIFIED EXPOSURE

Many creators defend these videos by pointing to what they gave.

★ Money.

★ Food.

★ Rent.

★ School fees.

They speak as though aid purchases ownership over another person’s image and story.

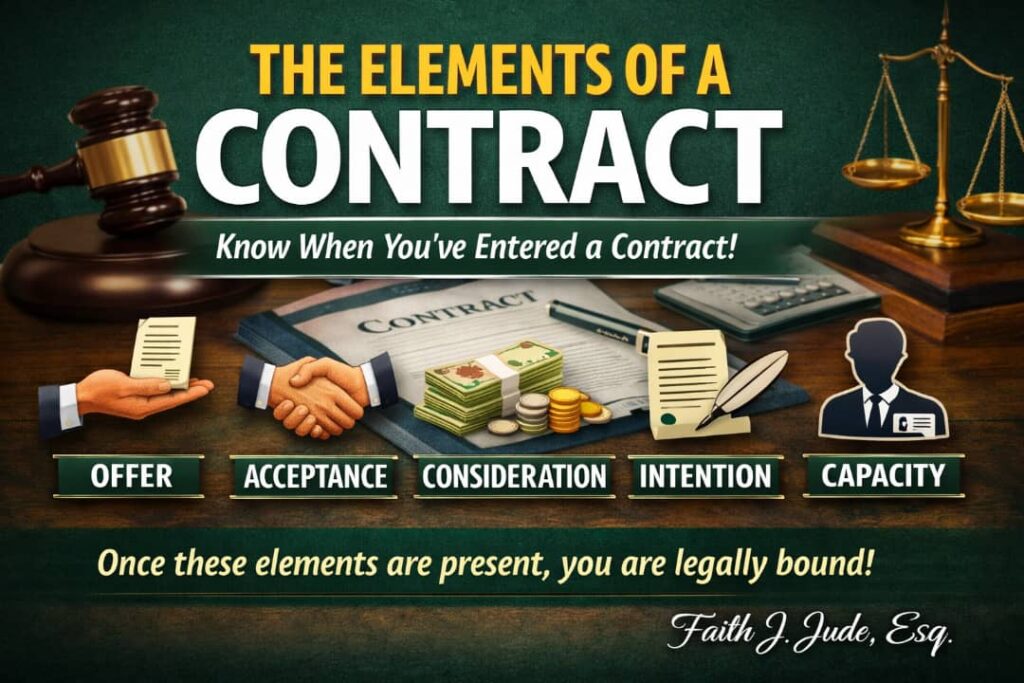

Under Nigerian law, help does not cancel rights. A person does not lose dignity because they accepted assistance. Charity is not a contract that transfers identity.

The Constitution does not say dignity is reserved for the comfortable. It belongs especially to the vulnerable.

THE TEEN MOTHER AND THE UNBLURRED FACES

One widely discussed scenario involved a teenage mother and her children filmed in a slum by a YouTuber who claimed to be improving their living conditions. The video showed their faces clearly. Their location was identifiable. Their story was told for them, not by them.

The legal issues here are serious.

First, the mother was still a minor. That alone triggers child protection obligations. Second, her children were exposed without safeguards. Third, the video created a permanent digital record of their poverty.

Even if assistance was given, the exposure cannot be undone.

Years from now, those children will grow. They will attend school. They will seek work. Their classmates and employers may find that video. Their worst moment will still be circulating.

This is harm with a long shadow.

THE CHILD RIGHTS ACT AND THE DUTY TO PROTECT

The Child Rights Act demands that every action concerning a child prioritise the child’s best interest. Broadcasting a child’s hardship for content fails this test.

It does not matter whether the intention was awareness or charity. The outcome is exposure. The law judges outcomes.

A child deserves protection from future embarrassment, stigma, and danger. Filming them in vulnerable conditions without anonymity violates that duty.

WHY BLURRING MATTERS

Some argue that blurring faces removes authenticity. That audiences want to see real people.

The law does not care about authenticity. It cares about protection.

Blurring faces, concealing locations, changing names are basic safeguards. They are not optional courtesies. They are responsibilities.

A person can be helped without being identifiable. If help depends on exposure, then help is not the priority.

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL COST TO THE EXPOSED

Several individuals interviewed during this social check spoke of shame that lingered long after the food was eaten and the money spent.

A young woman in Aba said strangers message her daily because of a charity video posted three years ago. She said she feels trapped by a past she cannot erase.

A man in Ilorin said he stopped leaving his house after people began calling him by a nickname from a viral video.

These are not statistics. They are lives.

CHRISTIAN CHARITY WITHOUT SPECTACLE

Christian teaching does not forbid helping publicly. It forbids helping to be seen.

There is a difference.

Helping to inspire others while protecting identity is possible. Helping to build personal brand at the expense of dignity is not love. It is pride.

If a person’s pain becomes your advertisement, something has gone wrong.

THE LAW IS CATCHING UP

For a long time, these practices thrived because enforcement lagged behind technology. That gap is closing.

Courts are becoming more sensitive to digital harm. Regulators are paying attention. Society is less amused.

Creators who believe charity content places them above the law are mistaken.

THE MORAL QUESTION NO ONE CAN ESCAPE

Strip away the algorithms. Remove the money. Silence the applause.

Would you still help if no one was watching?

If the answer is no, then the act was never about kindness.

FROM LAUGHTER TO COURTROOMS: PRANKS, HUMILIATION, AND THE LAW

There is a sentence Nigerians repeat often when harm has already been done. It was just a joke.

Those five words have excused broken bones, panic attacks, public shame, and lasting trauma. They are spoken with a shrug, as though laughter is a legal shield. It is not.

Prank culture has exploded in Nigeria’s social media space. Strangers are startled, insulted, chased, falsely accused, mocked, or frightened for views. The crowd laughs. The video trends. Money is made. Then something goes wrong.

And suddenly the same society that laughed begins to ask for mercy.

WHEN A JOKE STOPS BEING A JOKE

Under Nigerian law, intention to amuse does not erase responsibility for harm. A prank becomes unlawful the moment it causes fear, distress, humiliation, injury, or breach of peace.

If a person reasonably believes they are in danger, the joke has failed. If a person is publicly shamed, the joke has crossed a legal line. If a prank leads to physical injury, property damage, or emotional trauma, the law does not care that the audience laughed.

Laughter is not consent.

CRIMINAL LIABILITY AND PUBLIC ORDER

Nigeria’s criminal laws prohibit conduct that disturbs public peace, causes fear, or leads to disorder. A prank staged in public that provokes panic, alarm, or confrontation can amount to a criminal offence.

Creators often forget this. They see streets as sets and strangers as props. But public spaces belong to everyone. No one owes you participation in your content.

If a prank triggers a fight, stampede, accident, or police response, responsibility does not disappear because a camera was rolling.

PUBLIC HUMILIATION AND CIVIL CONSEQUENCES

Beyond criminal liability, public humiliation opens the door to civil claims. A person whose dignity is damaged by being mocked or exposed can seek damages.

Being laughed at by thousands online is not harmless. Reputation, mental health, and personal safety can be affected. Nigerian courts recognise that humiliation is a real injury.

The fact that a creator earns money from such content strengthens, rather than weakens, the case against them.

THE DANGEROUS SHIFT IN PUBLIC SYMPATHY

There is a familiar pattern.

A prank video trends. People laugh. Then the victim reacts strongly. Maybe they fight back. Maybe they collapse. Maybe they involve the police. Suddenly the narrative changes.

“Justice for the influencer”.

“The law is too harsh”.

“He is just a content creator trying to feed his family”.

“So people cannot create content in peace again”.

This shift reveals something troubling, sympathy is redirected from the harmed to the harmer. The victim disappears. The creator becomes the centre of concern.

The law does not operate on sympathy. It operates on facts.

YOUR RIGHTS END WHERE ANOTHER PERSON’S BEGIN

Freedom of expression is not absolute. Nigerian law balances it against other rights, including dignity, security, and privacy.

You do not have the right to frighten someone for content.

You do not have the right to insult a stranger publicly.

You do not have the right to turn another person’s fear into income.

Your freedom ends where another person’s rights begin. This is not oppression. It is coexistence.

VOICES FROM THE STREET

A market woman in Onitsha said she stopped going out early because of prank videos. She said she is tired of being frightened for amusement.

A young man in Lagos said he was punched during a prank because the target thought he was being robbed. He said the laughter stopped immediately.

A police officer interviewed said prank related calls waste resources and escalate tensions. He said cameras do not excuse disorder.

CHRISTIAN MORALITY AND MOCKERY

Christian teaching does not celebrate humiliation. It does not mock fear. It does not profit from embarrassment.

Laughter that requires another person’s pain is not innocent. It is cruelty dressed as comedy.

If your joke depends on someone else feeling small, afraid, or ashamed, it is not humour. It is dominance.

WHEN THE LAW FINALLY KNOCKS

Many creators believe consequences are unlikely. They see others get away with it. They feel untouchable.

But law enforcement works slowly, not blindly. Patterns are noticed. Complaints accumulate. Precedents form.

When the law finally knocks, it does not care how many followers you have.

ACCOUNTABILITY, ENFORCEMENT, AND THE LIE WE TELL OURSELVES

There is a lie Nigerians repeat whenever the law finally intervenes. “The law is too harsh”.

It is said when a content creator is arrested. It is said when charges are filed. It is said when courts insist that rights matter. The phrase is spoken with emotion, with familiarity, and often with selective memory.

What is rarely asked is this. Harsh to whom?

Harsh to the influencer whose income is threatened? Or harsh to the victim whose dignity was stripped, whose face was broadcast, whose fear became entertainment?

The law does not exist to protect comfort. It exists to restrain harm.

WHY SOCIETY DEFENDS THE WRONG PERSON

When content causes harm, public sympathy often shifts away from the injured and toward the creator. The creator is visible. They have followers. They have a voice. The victim usually does not.

This imbalance distorts justice.

We see the influencer crying online, apologising, explaining, blaming poverty, blaming pressure, blaming algorithms, blaming unemployment, blaming the government. We rarely see the victim again. Their pain does not trend. The society does not care.

Nigerian society has become emotionally attached to content creators as personalities. This attachment clouds judgement.

But the law is not a fan.

THE INFLUENCER DEFENCE

There is an emerging argument heard in public discourse. He is just a content creator trying to feed his family.

This argument is dangerous.

Many Nigerians are trying to feed their families. They do not humiliate strangers to do it. Poverty does not create special legal exemptions.

If earning money justified rights violations, then theft, fraud, kidnapping, and harassment would all be excusable.

The law rejects this logic.

ROLE OF LAW ENFORCEMENT

Law enforcement in Nigeria faces real challenges.

★ Limited resources.

★ Public pressure.

★ Misinformation.

But these challenges do not erase duty.

When citizens report violations, when evidence is clear, enforcement must follow. Selective enforcement weakens public trust.

Arrests are not persecution. Investigations are not oppression. They are process.

THE ROLE OF COURTS

Courts exist to balance competing rights. Freedom of expression is weighed against dignity, privacy, and security.

Nigerian courts have repeatedly affirmed that no right is absolute. Where expression causes harm, restraint is lawful.

Judges are not hostile to creativity. They are hostile to abuse.

REGULATORS AND DIGITAL RESPONSIBILITY

Regulatory bodies are beginning to confront digital harm. Data protection authorities recognise that online exposure can be as damaging as physical injury.

Platforms may be foreign, but harm is local. Nigerian regulators are increasingly asserting jurisdiction where Nigerian citizens are affected.

Creators who believe online space is lawless are mistaken.

THE ROLE OF THE PUBLIC

Accountability does not rest with institutions alone. Audiences have power.

What you watch, share, and applaud shapes behaviour. When humiliation trends, it multiplies. When dignity is rewarded, it grows.

Silence is not neutrality. Sharing harmful content makes one complicit.

CHRISTIAN RESPONSIBILITY AND SOCIAL CONSCIENCE

Christian teaching emphasises responsibility for one another. It warns against causing others to stumble. It condemns exploitation of the weak.

Supporting content that humiliates others contradicts this teaching.

Faith without conscience is empty.

A FINAL QUESTION OF FAIRNESS

Is it fair to hold creators accountable?

Fairness is not measured by convenience. It is measured by protection.

Those harmed by content rarely asked to be part of it. They did not agree to become lessons. They did not volunteer to suffer publicly.

The law stands with them.

STORIES THE CAMERA NEVER RETURNS TO

Behind every viral video is a person whose life continues after the upload. The internet moves on. The subject does not.

This part of the article draws from conversations, interviews, and informal surveys conducted during this social check. Names have been changed. Locations are generalised. Identities are protected. Not because the stories are weak, but because dignity still matters here.

THE WOMAN WHO STOPPED LEAVING HER HOUSE

She was filmed receiving food aid during a difficult period. The video showed her crying. The caption spoke of hope and transformation.

At first, she was grateful. Then the messages began.

People recognised her on the street. Some mocked her. Some asked intrusive questions. Some demanded money, believing she had received more than she did.

She said she stopped attending church regularly because she felt watched. She stopped going to the market alone. She said help ended, but exposure did not.

She was never asked how she felt about the video after it went viral.

THE MAN WHO BECAME A MEME

A young man in Lagos was pranked on camera. The video was edited with laughter and sound effects. His fear became entertainment.

Within days, clips were circulating without context. His face became a joke. His name was replaced by captions.

He said he lost a job opportunity after the employer saw the video. He said people treated him like a character, not a person.

He was told to relax. It was just content.

THE TEENAGER WHO GREW UP ONLINE

A teenage girl appeared in a charity video with her baby. Her face was clear. Her story was narrated by someone else.

Years later, classmates found the video. She said the comments hurt more than the poverty ever did.

She asked a question that stayed with the interviewer. Why did helping me require the whole world to see me like that?

CREATORS WHO REGRET TOO LATE

Not all harm is committed without conscience.

One content creator interviewed admitted that he chased virality without thinking of consequences. He said he believed the ends justified the means.

When someone he filmed asked him to take a video down months later, he refused. The video was still earning.

He said he regrets it now. He said he traded someone’s dignity for numbers.

Regret, however, does not erase damage.

THE SILENCE OF THE HARMED

Many victims do not speak publicly. They fear ridicule. They fear being accused of ingratitude. They fear being told they should be grateful for help.

This silence creates the illusion that harm is rare.

It is not.

WHAT THESE STORIES TEACH

They teach that harm does not end with the upload. They teach that dignity, once stripped, is hard to restore. They teach that law often arrives late, but memory does not fade.

Christian teaching speaks of restoring the broken quietly. These stories show what happens when restoration is replaced with exhibition.

THE WEIGHT OF WITNESS

Listening to these stories changes perspective. It becomes harder to laugh casually. Harder to share thoughtlessly. Harder to excuse cruelty.

The law exists because stories like these exist.

HELP WITHOUT HARM: ETHICAL AND LAWFUL CONTENT CREATION

Creating content in Nigeria is not inherently wrong. Helping others is not wrong. Telling stories is not wrong. The problem is the approach.

Creators must understand that the person they film is not a subject for views. They are human beings with rights, dignity, and feelings.

CONSENT AS FOUNDATION

No content should be recorded or shared without consent when it exposes someone’s identity, vulnerability, or private circumstances.

Consent must be informed. The person should understand how the content will be used. They should have the right to withdraw consent at any time.

Consent is not optional. It is the foundation of lawful content creation.

PROTECTING IDENTITY

When working with vulnerable people, children, or minors, identity protection is mandatory.

Faces should be blurred. Names should be changed. Locations should be generalised. Any content that could create lasting harm must be carefully considered. Consent in this circumstance should not even be considered. A person in need will obviously agree to anything just to survive.

This is not merely politeness. It is duty.

PRIVACY AND DIGNITY FIRST

Helping a person does not require broadcasting their struggles.

Aid can be given quietly. Charity can be effective without becoming a video.

The moment dignity is traded for content, ethics and law are violated.

BEYOND LEGAL MINIMUMS

Lawful conduct is not the same as moral conduct. Even if consent is technically obtained, creators must ask whether exposure serves the person or themselves.

Christian teaching emphasises helping without seeking reward. If the video exists primarily for followers, clicks, or applause, the act ceases to be purely charitable and becomes self-serving.

BALANCING TRANSPARENCY AND PROTECTION

Creators often claim that visibility raises awareness and encourages giving. This is true. But visibility does not require humiliation.

Stories can be told with respect. Successes can be highlighted without exposing the vulnerable to shame. The story belongs to the person first, the creator second.

SOCIAL MEDIA ETHICS IN PRACTICE

Some practical guidelines include:

- Ask permission before filming.

- Explain purpose and scope of publication.

- Give the subject control over their story.

- Avoid filming minors without legal safeguards.

- Blur or anonymise identities when harm is possible.

- Reflect on motives: is this to help or to grow personal brand?

- Remove content if the subject requests.

These steps are simple. They are human. They are lawful.

RESPONSIBILITY TO AUDIENCE

Audiences have a role too. Sharing videos that expose or humiliate others perpetuates harm.

Creators and audiences together shape culture. If society applauds cruelty, creators will produce it. If society values dignity, creators will protect it.

THE LONG VIEW

Ethical content creation recognises that today’s viral video may be tomorrow’s regret.

Helping quietly may seem less spectacular, but it changes lives without harm. Law, morality, and conscience align when dignity is preserved.

CONCLUSION:

DIGNITY BEFORE VIRALITY

The business of vulnerability is profitable because society allows it. Content creators see pain, grief, and poverty as material. Audiences consume it eagerly. Silence from the law and bystanders encourages the pattern.

But law, morality, and conscience converge to remind us that this cannot continue without consequence.

Nigerian law protects dignity.

★ Consent is required.

★ Privacy is enforceable.

★ Children are specially protected.

★ Harm done to one person can trigger both criminal and civil liability.

Being a creator, being poor, being entertaining, or having good intentions does not negate these obligations.

Christian teaching reinforces this with quiet force. Respect for others, helping without seeking reward, preserving the dignity of those in your care, and offering assistance discreetly are not outdated ideas. They are timeless principles that protect both giver and receiver.

The stories collected in this social check show the human cost when these principles are ignored.

★ Lives disrupted.

★ Shame immortalised.

★ Opportunities lost.

★ Trauma amplified.

★ Regret accumulating.

The responsibility is shared.

★ Creators must choose ethics over virality.

★ Audiences must choose empathy over amusement.

★ Regulators and law enforcement must act consistently.

★ Society must refuse to celebrate harm as entertainment.

Dignity before virality is not just a slogan, it is a moral and legal imperative. Every video, every post, every story that involves another human being must be measured against this principle.

In the social media era, it is too easy to forget that behind every view is a life. That behind every like is a person. That behind every viral moment is a choice.

Choose wisely. Choose humanity.